Export finance in a nutshell

The world’s economies are increasingly interlinked, and so growing companies and governments often decide to import equipment or machinery from a different country to improve their productive capacity or efficiency. These importers can range from a small textiles manufacturer to a big energy producer or a major government ministry. As with any investment, buyers can choose to finance these purchases either to conserve their cash flow, or because the investment is too large for them to fund from internal sources.

Financing these purchases might be difficult for a number of reasons:

The buyer is located in a country that is politically unstable

The assets use relatively new technology that might not perform as promised

The buyer might be at risk of not being able to repay its loans

These issues might prevent a buyer from being able to finance that purchase, so almost every major exporting country has put mechanisms in place to try to mitigate these issues, and make lenders and exporters comfortable, so that a purchase can take place, and those exports can contribute to increased employment in the exporting country.

The main mechanisms governments use are export credit agencies (ECAs). These can be a government department (as in the UK and the USA, for example), a company in which the government is the majority shareholder (eg Spain) or private companies that manage these risks on behalf of the government (eg Germany or the Netherlands).

ECAs typically issue lenders with insurance policies, with the buyer paying a fee to the ECA to insure a loan linked to a supply contract, and the lender/s getting reimbursed by the ECA if the borrower is unwilling or unable to make repayments under that loan. ECAs do not cover 100% of any loan, leaving a residual risk with the lender/s of around 1-5%.

TXF considers a transaction an export financing if all or part of that transaction features at least one ECA.

Rules

The availability and cost of financing can be so important to a buyer that in some instances they will consider purchasing from a country depending more on the attached ECA support than on the actual price of the exported goods. This could encourage larger countries with healthier finances to engage in anti-competitive behaviour by offering lower-cost debt or more generous terms and conditions.

As a result, a majority of ECAs agreed to follow rules set by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In this agreement there are rules on minimum fees and maximum debt maturities that together promote a level playing field for all participating countries.

With reference to the OECD agreement, it should be possible to calculate, for example, the minimum fee that a borrower would pay to insure an export credit, and even the interest rate of the loan, in certain instances.

Products

In the first section above we discussed the basics of ECA finance, but ECAs can help promote exports in more than one way. There are several products that ECAs typically use:

Buyer credit

This is the solution described above, under which ECAs insure a credit or loan used to pay for goods supplied by exporters.

Supplier credit

If an exporter receives a particularly large order it may itself need to borrow to make the investments in raw materials, staff and equipment necessary to fulfil that order. This product gives exporters access to liquidity to enable them to take on contracts.

ECA direct loan

In some cases ECAs prefer to lend the money themselves rather than rely on banks. In that case the ECA takes on all the credit risk associated with a borrower. Most ECAs prefer not to take this risk, but sometimes find it to be more cost effective, for instance when making smaller loans to smaller customers. They may also be forced to step in when a general liquidity crisis prevents banks from making any loans at all, regardless of the cover they carry, as happened in the 2008 financial crisis.

ECA guarantee

This product is sometimes referred to as a performance bond. It is a guarantee issued on behalf of an exporter specifying compensation to the customer if the exporter does not honour all or part of its contract.

There are other products that some ECAs offer in addition to this, but they tend to be adaptations of the four products listed above.

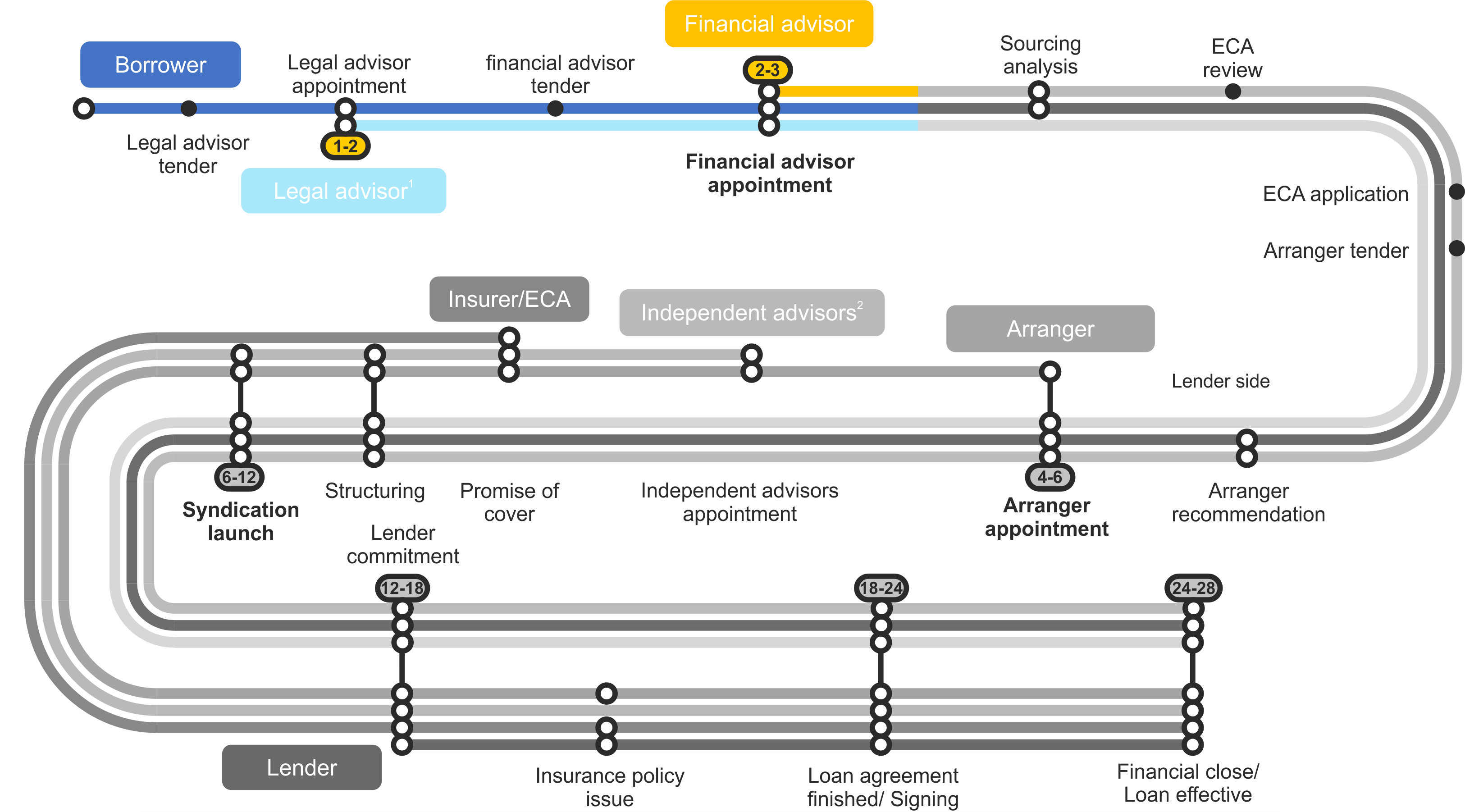

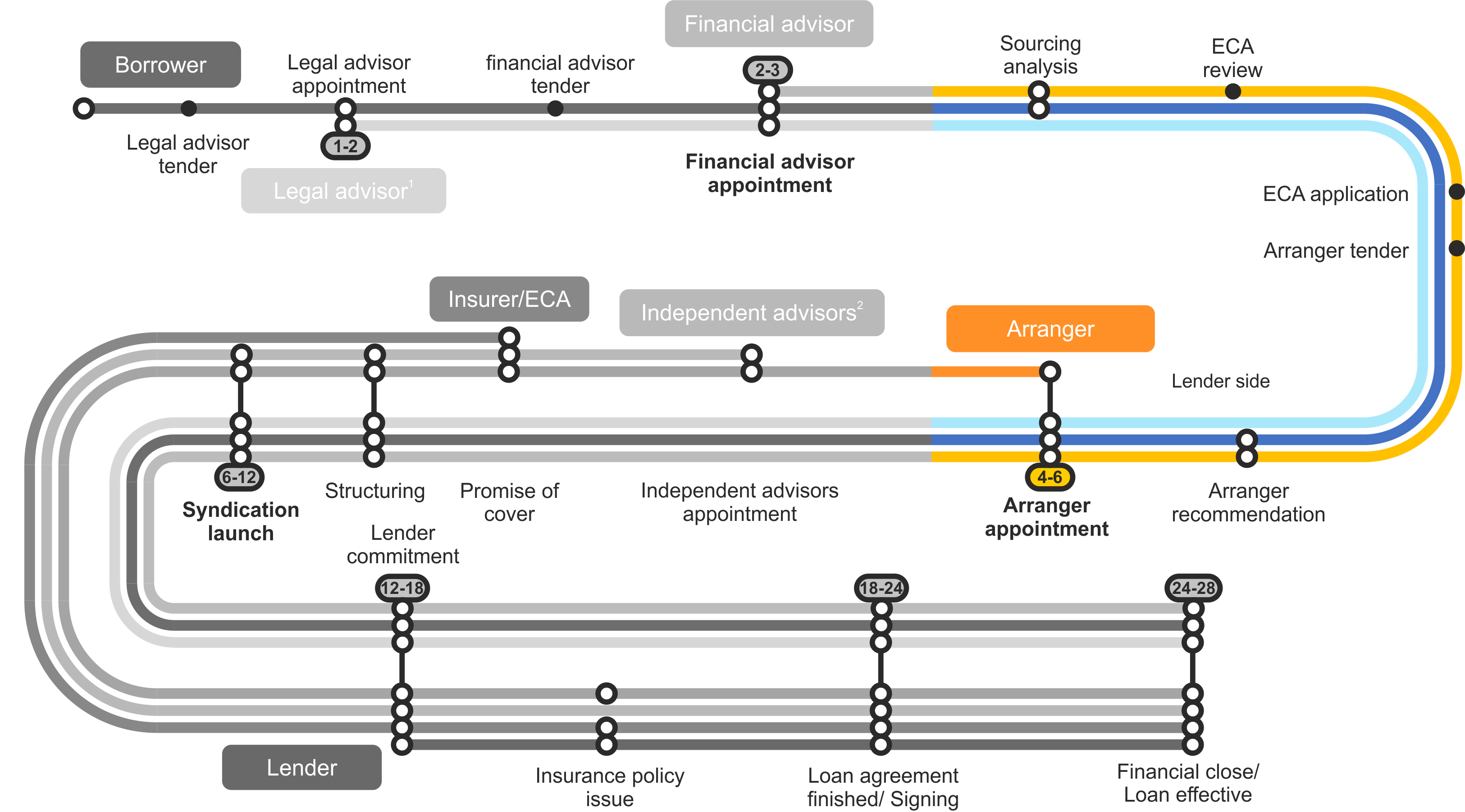

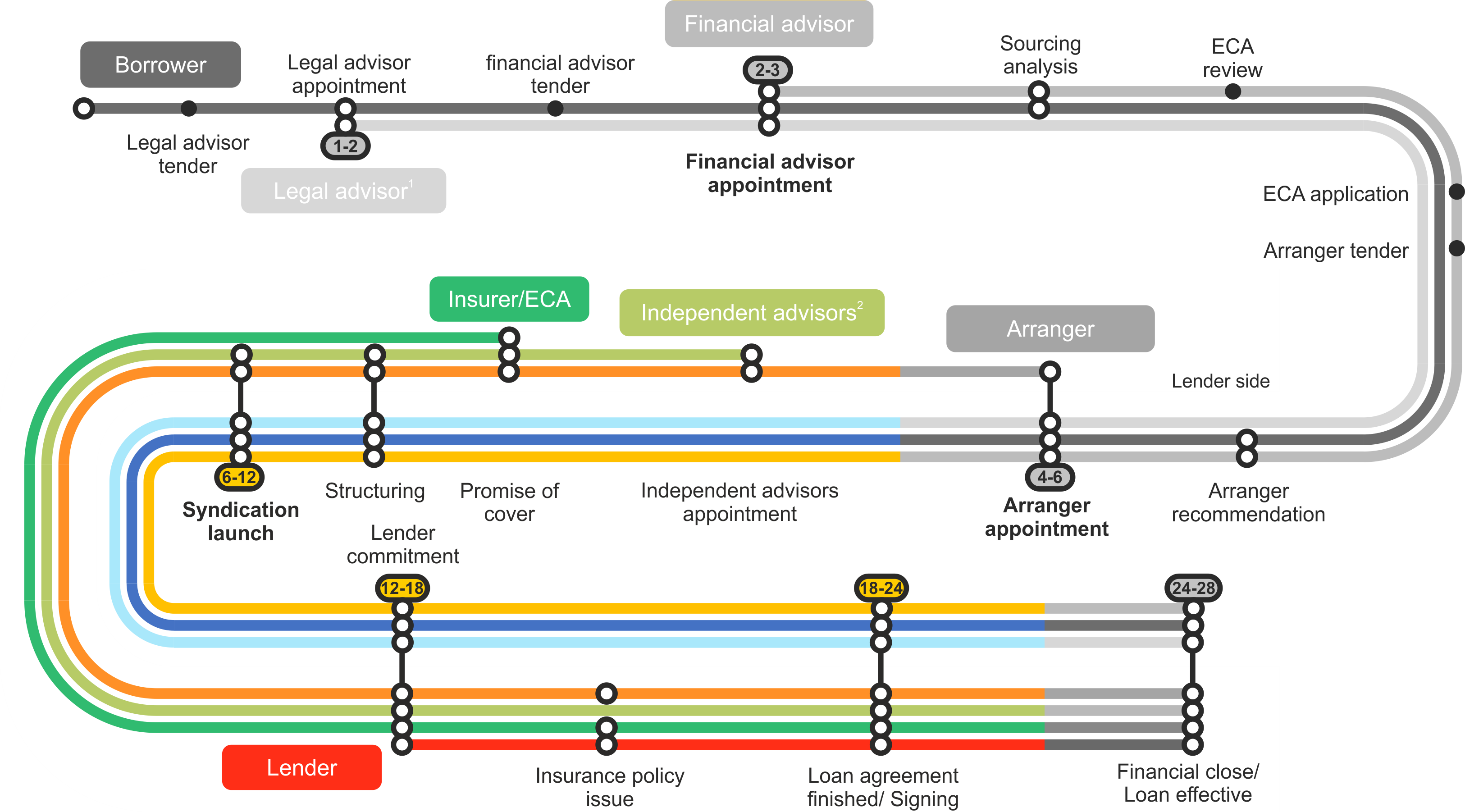

Buyer credit. Main steps and timeline

Buyer credits are the products most frequently used by buyers looking for long-term financing - and feature the most complex financial structures, in terms of the number of parties involved. These transactions go through a process that can take as long as 2 years to reach financial close. The main steps are as follows:

1. Feasibility

In this stage the borrower or buyer tests the market’s appetite for the deal, normally with the help of a financial advisor. This process can be very formal and linear, as in the illustration above, and the borrower looks for legal representation and then for a financial advisor. Sometimes the borrower already has a relationship with a financial advisor and this process does not happen at all. Some exporters may even have a team in place to assist customers with financing. Once the financial advisor is appointed, it will prepare some basic information on the desired financing to present to ECAs, so they have a sense of the terms and conditions of the deal. In this stage a deal could be considered too risky, or even not risky enough to require ECA involvement. In those instances there is no need for credit insurance at all, because banks are comfortable with the risk and the extra cost of the insurance does not make sense.

This process can take up to 3 months.

2. Structuring

Once the transaction looks feasible, the financial advisor does a full sourcing analysis of the asset/project. Because some components can be manufactured in several countries it is common to explore options from multiple countries. At the same time the buyer and financial advisor will start talks with ECAs. Once the buyer has chosen its suppliers the financial advisor will start the application process with ECAs, and will launch a tender for an arranger for the financing if the financial advisor is not going to take on that role. Once it has received all of its arranger responses, the financial advisor issues a recommendation, and the borrower appoints - or mandates - an arranger. This typically happens 4 to 6 months into the process.

3. Execution

The arranger then assembles a transaction by drawing on the expertise of advisors on different aspects of the deal (legal, environmental, technica, and so on) and finding additional lenders if necessary to provide some of the transaction’s debt requirement. This process - of making all parties comfortable with the financing terms - involves a lot of administration and coordination. In this process lender/s, guarantor, buyer and seller may each give official notice that it is committing to the deal. For instance ECAs will issue promises of cover, and lenders may issue a commitment letter until all parties are ready to sign the loan agreement. This can take as long as 24 months on complex deals where multiple ECAs and lenders are involved.

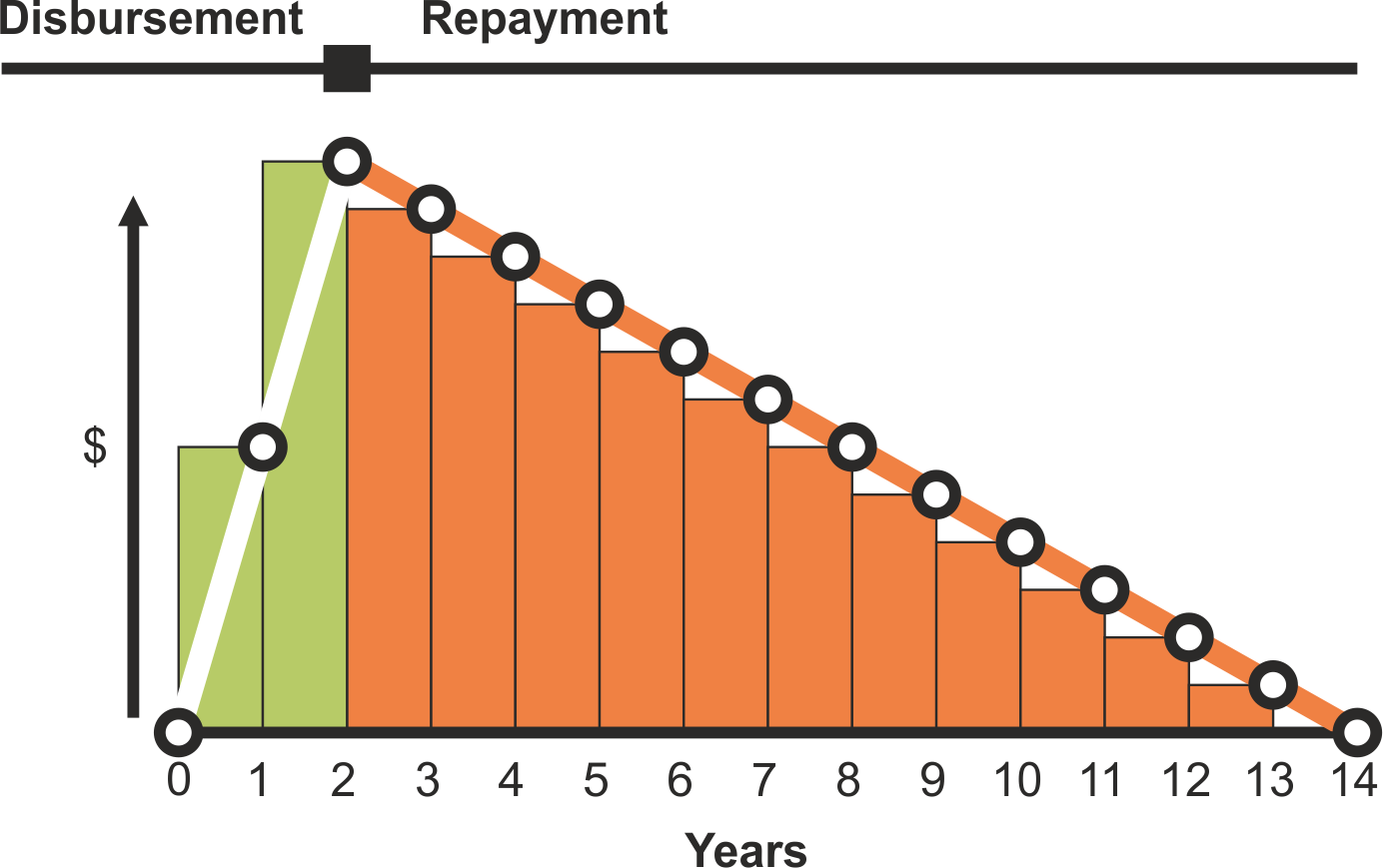

4. Draw down, repayment and monitoring

After this lengthy process culminates in the signing of loan documents, the borrower has access to the funds needed to make the purchase of the equipment, but the loan agreement does not become effective until the borrower draws at least part of the funds. The life of the loan consists of two parts:

- Disbursement: The buyer/borrower starts to draw down money from the lenders in one or several instalments. This is usually the riskiest period of the life of the loan for the lenders, so they normally supervise the progress of the construction/manufacturing of the assets or project and only disburse additional funds once certain milestones are reached.

- Repayment: When, or shortly after, the borrower takes delivery of an asset, they start paying back the loan (principal + interest). These payments typically happen every 6 months, but their frequency can vary depending on the agreement.

The loan timeline can be simplified and represented as follows:

The loan timeline can be simplified and represented as the chart you can see on the right, where we have 2 years of disbursement and 12 of repayment. Green represents funds going from the lender to the borrower and red the opposite.

Types of recourse and structuring

In finance there are three basic ways that a deal can be structured in terms of the rights of the lenders over the assets of the borrower:

Non-recourse

Lenders only have the right to repossess the assets covered by the loan agreement, and do not benefit from any other support from the purchaser’s corporate parent or its shareholder/s

Limited recourse

Lenders may benefit from some support from the borrower’s parent or shareholders, in terms of guarantees of some obligations, or its support is time-limited (say until the asset enters operations).

Full recourse

The borrower may be the corporate parent, or the borrower benefits from full guarantees from a corporate parent or related company, and lenders benefit from an unconditional obligation to repay the loan (and sometimes security over their assets) until the debt is paid in full

Export finance also uses these different types of recourse depending on the nature of the asset, and normally deals are structured so they are:

- Corporate finance: Typically lender/s have full recourse to the assets of the borrower (or its parent) in these loans. Some asset classes such as aircraft and ships might be financed based purely on their market value if they can easily be re-sold and moved and the loan is smaller than the expected value of the asset. This ratio is called loan to value, or LTV, and it is expressed as the loan amount divided by the asset value in %)

- Sovereign finance: When the borrower is a government or a public company and the repayment obligation is that of the government. This is potentially less risky than corporate finance, because a host government has more resources at its disposal than most companies and governments do not normally default. But it is much harder for lenders to seize the assets of a sovereign government when something goes wrong.

- Project finance: Project finance structures are designed to confine the risks associated with the acquisition, construction and operation of a specified project or asset to that asset. Lenders will only have recourse to the assets within the project finance scope, so these risks tend to be managed and allocated through a series of tightly negotiated contracts. Most importantly, these will often include a construction contract and an offtake agreement to manage construction and revenue risk, respectively. Alternatively, lenders might benefit from regular payments from a third party, for instance a lease for an oil rig or an availability payment for a piece of public infrastructure like a school. The owner of the project is only at risk of losing that project if the project defaults, rather than having to make additional payments to lenders to make them whole, as would be the case for a corporate financing. Project finance loans are normally non-recourse and sometimes limited recourse as outlined above. The owner/s or developer/s of a project create a separate company just to own that asset, and as shareholders are known as the sponsors of that project. These separate companies are known as special purpose vehicles or SPVs. The SPV’s contracts assign rights and obligations to lenders and sponsors. The term project finance is more characterised by its non-recourse nature than the assets being financed, which are often infrastructure projects, but can be other assets that benefit from long-term contracts such as ships or aircraft. At the same time some infrastructure projects are financed using corporate or sovereign debt and not using non-recourse project finance loans.

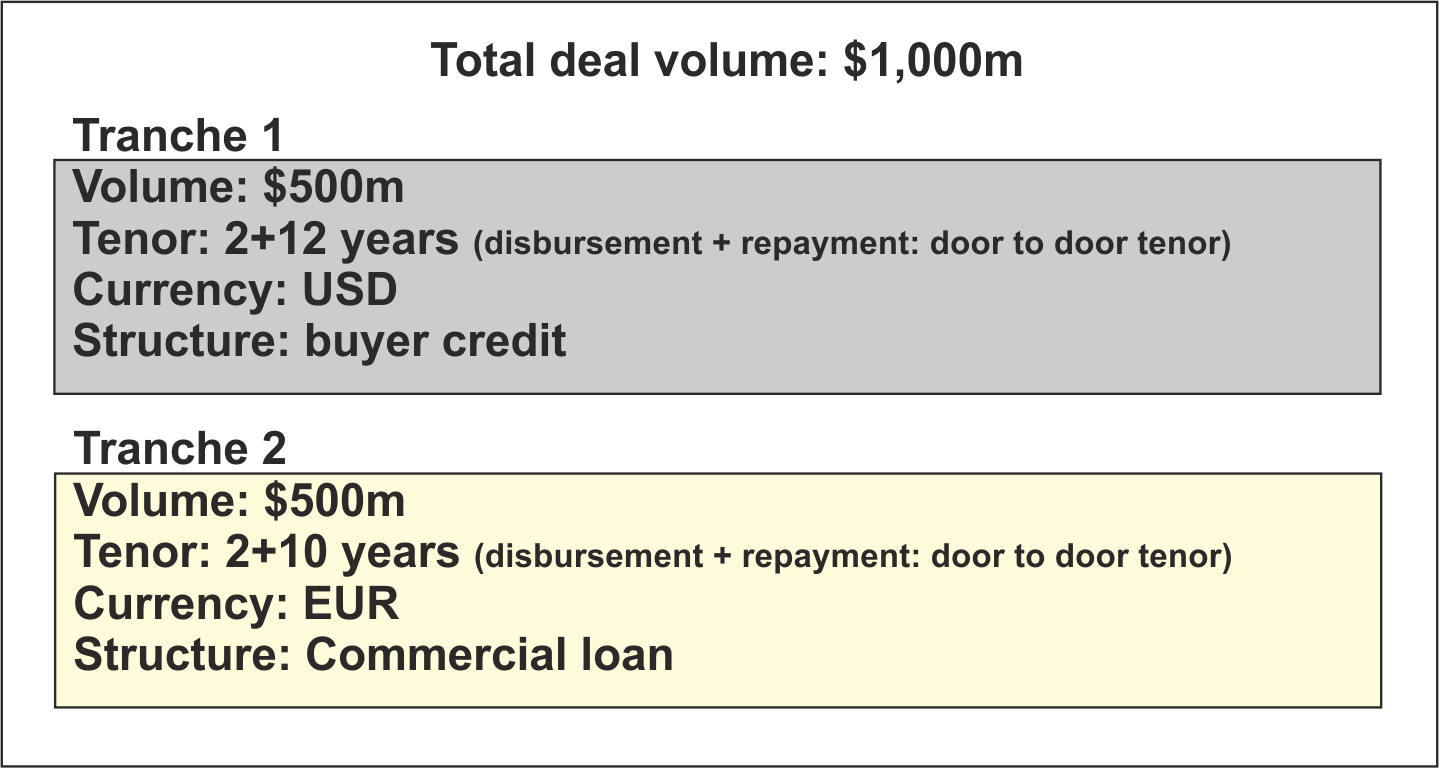

Tranches

Very often an export finance transaction can be too large for a single lender or even an ECA to feel comfortable assuming all of the risk. Different bank lenders in export finance have widely different limits on their participation in deals, but a reasonable average would be between $100m and $150m.

ECAs have even more widely different transaction limits, and these may vary by borrower and/or host country. Another likely scenario is where a purchaser decides to source its equipment from more than one country, meaning that more than one ECA is involved. Different lenders and in particular ECAs will attach different sets of terms and conditions or maturities on loans. As a result transactions are frequently divided into different tranches.

These tranches will typically each have its own set of conditions, currency, maturity or pricing, and their own lending groups, and usually a single ECA as primary guarantor. In export finance tranches allow lenders to choose which ECA they are most interested in lending under or alongside. It is very common for lenders, particularly the larger ones, to participate in multiple or all tranches, though it is also common for banks to participate in just one tranche.

A common terms agreement will usually govern relationships between a transaction’s different tranches’ lenders. In conventional finance, a tranche may also denote claims over assets or revenues of different priorities (i.e. who gets paid first, and who can foreclose over particular assets), but this is not necessarily the case in export finance.

If you visit TXF Intelligence’s database there are plenty of examples, but a tranche breakdown would typically look as follows:

About TXF

Founded in 2013, TXF is a specialist B2B market intelligence provider in the trade, export, commodity and project finance sectors.

TXF provides financial institutions, law firms and corporates with the latest news, data, research and market-leading events that help our clients pursue their business objectives.

View our upcoming events or find out more about a TXF Intelligence subscription by clicking on the buttons below:

TXF Intelligence subscription Upcoming events