Trade risk: Venezuela has a future – but what?

In the wake of the illegitimate 20 May presidential elections, Venezuela is at an inflection point. The country faces an acute political and economic crisis, and the Maduro government’s long-term viability is low. For trade and export financiers, it is important to consider what comes next in Venezuela, and what signals will determine the country’s path.

Few countries present as grim a risk picture for exporters, lenders, insurers and investors as Venezuela. There are other countries that have recently over-extended themselves in a high-commodity price environment – Angola, Ghana, Zambia, Chad among them – but none have experienced the kind of economic collapse and political crisis that Venezuela is going through, nor have they declined from such heights of wealth as Venezuela had in the 1970s to the essentially failed state it is today. Venezuela thus provides a cautionary tale for risk managers assessing their global exposures and strategies.

For market participants, it is useful to consider how Venezuela arrived at its current crisis, what paths lay before it, and how new developments signal a change in Venezuela’s direction.

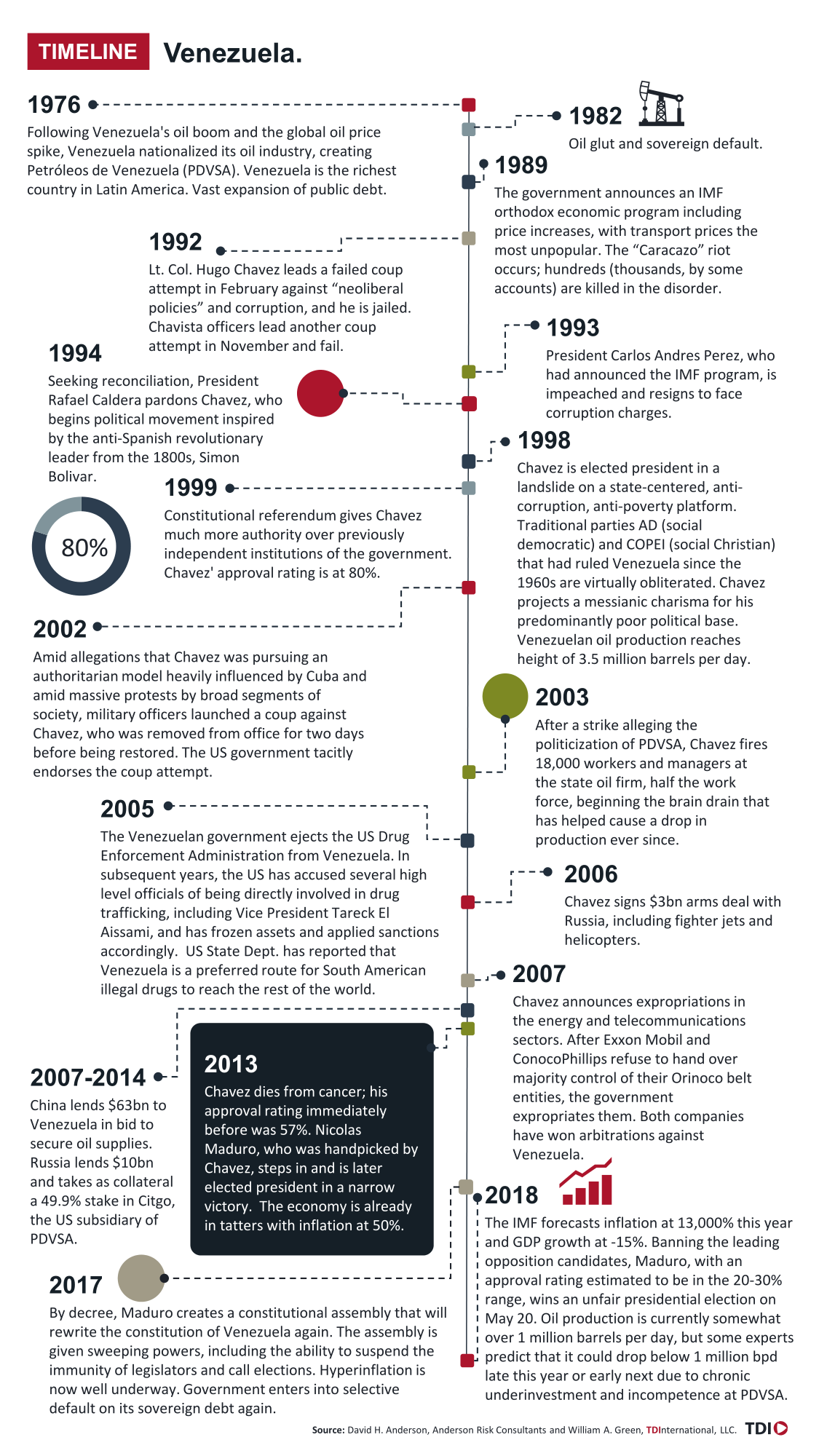

Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world, and oil accounts for 95% of export earnings. In large part, perceptions and mismanagement of this resource are the primary source of Venezuela’s political and economic problems. The commodity had a central role in establishing Venezuela as the wealthiest country in Latin America by the 1970s. In the 1980s, the oil glut and a subsequent sovereign default led to stagnation and declines in living standards, along with rising frustration among the poor majority. The subsequent victory of the populist socialist Hugo Chavez in 1998 elections, following his earlier attempted coup in 1992, saw the politicization of the state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), aggressive domestic social spending, and wasteful foreign policy financing initiatives – policies that were all dependent on oil prices around the $100 per barrel mark.

Chavez’s “Bolivarian revolution” bankrupted the country. Heavily influenced by Fidel Castro and the Cuban model, Chavez complemented his domestic agenda with a reorientation of Venezuela’s foreign policy away from its largest export market, the United States. Chavez’s chosen successor, Nicolas Maduro, doubled down on the same disastrous policies, driving away international investment, hampering economic development, and emptying state coffers, all while oil prices plunged starting in 2014. With its negative impact on good governance and accountability, corruption, which has always been a problem in Venezuela, has accelerated dramatically among senior military, security, and police officials and led to Venezuela becoming a key narcotrafficking hub.

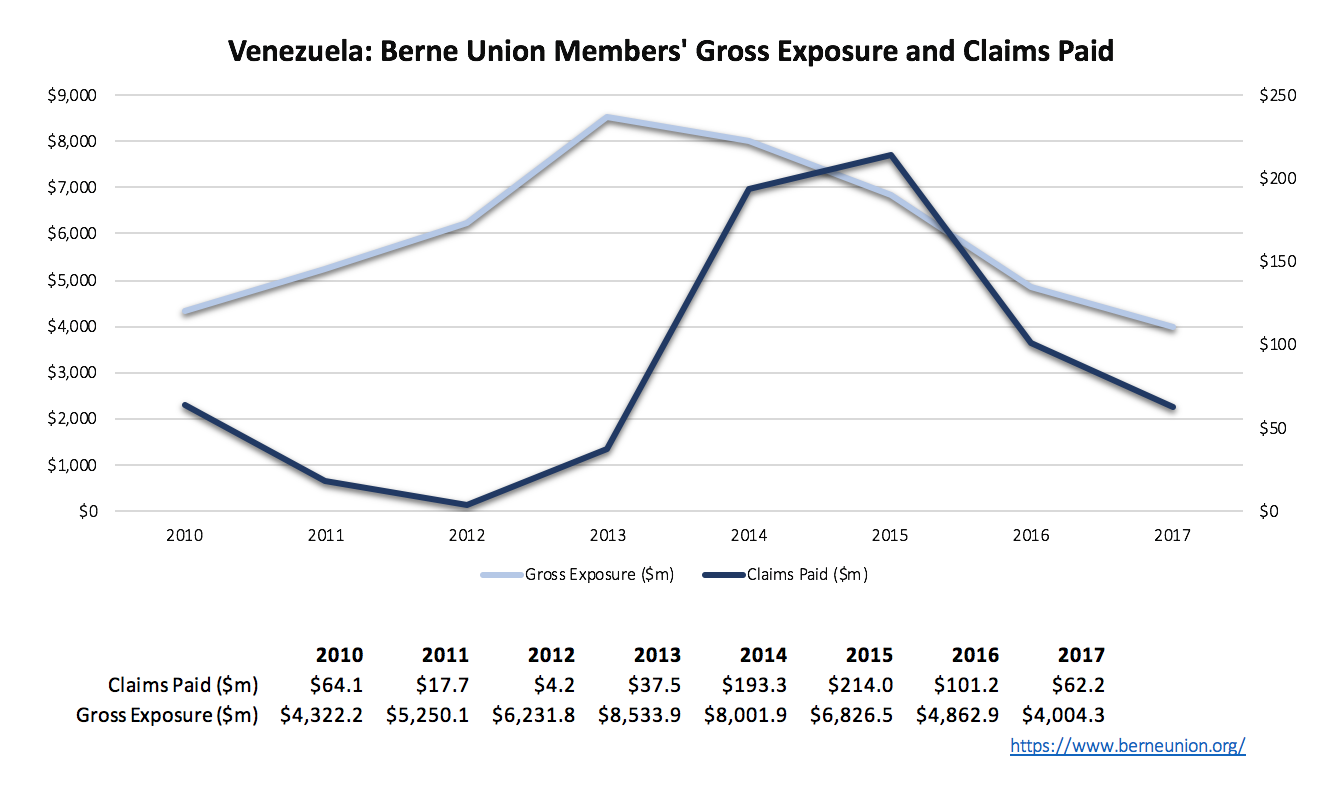

Venezuela’s major economic indicators are calamitous and accompany a growing internal humanitarian crisis and refugee exodus to neighboring states. Oil production has declined from a high of over 3 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2000 to 2.3 million bpd in 2016. Since then, production has fallen to about 1.4 million bpd today – 1.1 million bpd is exported, and half of the exports are used to repay Chinese and Russian loans, according to Asdrúbal Oliveros at Ecoanalítica in Caracas. With all the problems at PDVSA, daily production may fall below 1 million bpd by 2019. Hyperinflation is well-entrenched, and the IMF’s current estimate indicates inflation could rise to 13,000 percent this year.

Domestic and international influencers

The influencers and interlocutors in Venezuela are in flux, raising uncertainty in an already volatile jurisdiction; however, understanding the motives and capabilities of key factions is central to interpreting future developments.

Venezuela is effectively a one-party state with aggressive security services (augmented and influenced by Cuban intelligence) and a supportive military. The political elite around Maduro are members of the PSUV party and are largely committed to Chavez’s populist-socialist policies. The regime was always suspicious of the West and capitalism, but the 2002 failed coup, many mass protests, and ensuing economic collapse has encouraged further radicalization among high-level members of the regime. Against the regime is the majority-opposition-controlled National Assembly, but Maduro succeeded in containing it in March 2017 with the creation of the regime-controlled Constitutional Assembly tasked with rewriting the constitution.

The military high command, having been subject to multiple purges in the officer corps following the 2002 coup attempt, is the bedrock of the regime. High-ranking officers are rewarded based on political loyalty to Maduro, and mass promotions – including the 2016 promotion of 195 officers to the rank of general – and financial incentives inextricably link the top brass with Maduro’s fate. High-ranking officers hold ministerial positions, manage PDVSA, and are involved in corrupt food distribution programs, illicit trade, and narcotrafficking with Maduro’s approval. However, the economic crisis is so grave that desertions have risen to an alarming level, and the high command must be aware that its ability to deploy is decreasing by the day. How military officers, particularly at lower ranks, calculate their options is a major variable for Venezuela’s future.

Meanwhile, foreign governments have played a substantial role in shaping Caracas’ outlook. First among these is Cuba – alongside similar social and economic policies, Venezuela’s leadership has looked to Havana as a model authoritarian system to emulate. Trade in oil and the deployment of Cuban doctors and intelligence operatives in Venezuela cemented the shared ideological outlook. However, by a combination of design and circumstances, Venezuela has never made the full transition from authoritarianism to Cuban-style totalitarianism.

Early in Chavez’s regime, Beijing and Moscow saw both a business opportunity in Venezuela’s oil sector and a useful ideological foil against the US. China has provided $ 62 billion to Venezuela since 2007 as part of an oil-for-loans program according to Washington-based Inter-American Dialogue. Since 2016, Venezuela has only made interest payments. Russia’s state-owned Rosneft has similarly provided financing to PDVSA, secured by shares in PDVSA’s US-based refining and retail subsidiary, Citgo.

The United States, while diminished in influence since Chavez's election and the failed coup, remains an essential player by virtue of Venezuela’s dependence on oil exports to the US. Approximately 40% of Venezuelan exports remain destined for the US. Although there are some sanctions on Venezuelan officials, Washington has hesitated to stop purchasing Venezuelan oil due to the negative impact on Venezuelan civilians and US gulf coast refineries that exclusively process Venezuela’s heavy crude. If sanctions on oil purchases are adopted by the Trump administration, Maduro would lose one of his last major cash streams.

Scenarios for the next one to three years

In response to the collapsing economy, various players are calculating their positions, ultimately raising the volatility in Venezuela. One aspect is clear – the current system is unsustainable. The Chavez model was based almost exclusively on robust oil prices and the ability to distribute oil revenue to the population through social programs. That revenue stream has diminished substantially. Most of the population, which once believed in the “revolution,” has abandoned the government and only about 20 percent support Maduro. Likewise, Venezuela has no external partner that is prepared to prop up the regime.

Because of the continued degradation of the country’s economic and social circumstances, a scenario that sees Venezuela continue along the same path is untenable. Additionally, a scenario leading to civil war is unlikely and therefore excluded. Actual events are unlikely to perfectly mirror the below scenarios, but the exercise can identify key signals that market participants should consider, whether monitoring physical security developments, loan exposure, or risk insurance policies.

1) Ceausescu revisited (slow implosion):

Signals:

- Authoritarian rhetoric and political arrests continue;

- Oil price trends up from $75 per barrel, and oil technocrats are brought in to stabilize production; and

- Caracas manages to successfully challenge or delay pending arbitration enforcement awards and asset seizures by ConocoPhillips and other creditors.

The current selective default becomes a general sovereign default on all obligations. Caracas is increasingly isolated without the support of its political and economic allies. Cuba does not have the security resources to assist Maduro’s enforcement of his total control. Meanwhile, China is not interested in bailing out Maduro. Fearing blame for Venezuela's complete collapse, the US refrains from enacting a sanctions death blow. The National Assembly is effectively replaced by the Constitutional Assembly, and Maduro controls each branch of government.

Meanwhile, military desertions, which already required Maduro to call up retirees and reservists before the 20 May election, challenges the regime’s de facto control. The regime is able to keep a semblance of order in Caracas, other major cities, and around oil infrastructure, but outside these areas there is chaos and increasing desperation. In many areas, citizens respond by emigrating. Current migration rates may lead to 1.8 million people leaving Venezuela for neighboring states by the end of 2018. As food and medicine scarcity increases, this rate will rise.

Russia and China send technical advisors to assist. Functionally, Maduro retains enough control to formally remain in power and keeps enough oil flowing to buy loyalty from the elite and portions of the military. The military oversees and continues to benefit from truncated oil production and expands its involvement in illicit trade. The economy continues to deteriorate, and the humanitarian disaster expands.

The situation, while dire, resembles Romania in the 1980s, another oil producing economy under a heavy debt load that prioritized oil deliveries and repayment, while basic goods and food become unavailable. Even as the system slowly dissolves, the figurehead (Ceausescu in Romania, Maduro in Venezuela) is useful for third parties to pursue their economic interests. While unsustainable in the long-run, without external intervention or a unified opposition, it continues through the forecast period.

Implications for TXF readers: There is no realistic sovereign debt rescheduling or economic program on the table. Expropriations, widespread protests and violence in different parts of the country, and currency inconvertibility make almost all risks impossible to write. There is no reasonable way to negotiate with the government unless one is willing to put new money into the country, which no one is willing to do. Filing suit and arbitration are the main avenues here, together with coordinating with other creditors and pursuing the attachment of Venezuelan assets. Creditors with developmental or diplomatic goals (e.g. World Bank) will have to wait it out.

2) Mugabe-esque exit (coup d'etat):

Signals:

- Mass demonstrations erupt for several days at a time without security forces being willing or able to quell them;

- High-ranking military officers begin to make political statements in the media that are not consistent with normal “Bolivarian” rhetoric;

- Military desertions currently underway evolve into military challenges to the regime in major cities like Caracas, Valencia, or Maracaibo;

- US declares sanctions on oil shipments; and

- Creditors effectively seize significant Venezuelan assets, including refineries, ships, or even parts of Citgo.

Elements in the military, possibly officers below the high command who benefit less and less as the proceeds from illicit activities are reserved for senior officers, take matters into their own hands. Desperate from the economic circumstances and motivated by promises of a better future, lower ranks join. There are two sub-scenarios here: 1) the military plans and executes a coup from within, or 2) mass protests or a social movement prompts officers to turn on Maduro and refuse to repress demonstrators. The coup plotters may coordinate with a civilian leader, and a junta is likely to restore the National Assembly and promise free and fair elections.

Right now, the field is open for a new movement to capitalize on the illegitimacy of the regime. For example, the Frente Amplio Venezuela Libre earlier this year brought together opposition parties, former regime supporters, religious groups, and student groups to resist the regime. Neither Maduro nor the official opposition has broad support: two-thirds of the population reportedly believes neither the regime nor the opposition can stabilize the country.

In any case, in this scenario, the military coup leaders realize that reconciliation and some form of democracy is the most sustainable path forward for a prosperous Venezuela. They are ready to cede power to duly elected civilians under the right circumstances. Some military officers who will be subjected to criminal investigation quietly leave the country or are arrested.

In November 2017, Zimbabwe had a coup removing the long-time anti-Western autocrat Robert Mugabe, who presided over hyperinflation and draconian repression of all opposition groups. The Zimbabwean government is working toward elections in 2018, although risks to that outcome remain.

Implications for TXF readers:The military junta soon brings in technocrats to construct a debt strategy and a viable economic program, along with turning around PDVSA. Following elections, debt is restructured, and creditors are able to recover some of their losses over the long term. The new government may approach the former owners of expropriated property and may reach settlements. Risk remains high, and insurers and exporters will largely stay in a wait-and-see mode for new transactions during the forecast period, but there is some optimism by most observers that the country will be able to recover in the long run.

3) Mexico 2000 (relatively peaceful transition):

Signals:

- Maduro starts making very conciliatory speeches, moving from his normally divisive rhetoric to unifying and healing words;

- Meetings between Maduro's circle and opposition figureheads occur and are publicized; or

- Political prisoners are released.

Following the 20 May 2018 election that was boycotted by most of the opposition and declared illegitimate by international observers, Maduro realizes that his levers of power—oil production, oil money, popular support, and military power – are disintegrating, and he must negotiate. The main revelation may be prompted by a threat from the upper echelons of the military, which delivers an ultimatum that he must organize a transition, or he will be removed. Possibly, the US threatens oil sanctions. As a result, Maduro approaches the opposition in the National Assembly to initiate negotiations over the creation of a transitional government.

Independent experts from Venezuela have prepared various frameworks on which to base a transition plan, the majority of which would see a controlled period of Maduro formally remaining in power as a transition government is organized to take control. Once an internationally recognized government obtains power, international assistance, including IMF financing, will enable Venezuela’s stabilization and the pursuit of an economic reconstruction plan that reintegrates Venezuela into the global economy. This will be part of a long-term effort and is likely to feature amnesty for the former regime or military officers.

In 1999, President Ernesto Zedillo of Mexico, in a break with tradition, did not name a successor from his party, the PRI. The move was a reaction to the Mexican peso crisis, the PRI’s splintering, and signs of domestic instability. In 2000, for the first time since taking power in 1920, the PRI lost a presidential election to an opposition party and conducted a peaceful transfer of power.

Implications for TXF readers:The impact under this scenario will be somewhere between the Ceausescu and the Mugabe-esque Exit. While political reconciliation may have positive results, the outcome and timing are uncertain. It will not be immediately clear whether a competent team will lead economic reconstruction. Street violence continues unabated, as economic conditions continue to deteriorate. If the transition does come to fruition, then the longer-term outcome is similar to that of the Mugabe-esque Exit: creditors and investors will wait to see what the new government looks like.

The future goes beyond oil

Although much of our discussion focuses on what leaders will do in the context of economic collapse, much depends on the transition that the Venezuelan people have gone through. Historically, the effect of oil on Venezuela went well beyond the economic “oil curse” of crowding out private investment to a cultural belief in oil wealth as every Venezuelan's right. Building a competitive economy and institutions have been low priorities.

Now, however, the population of all income classes has witnessed an unprecedented economic disaster. This sort of hyperinflation, with every day a struggle for survival for most people, is forcing many to reconsider their assumptions. Perhaps the biggest question for Venezuela, then, is what conclusion most Venezuelans will draw from this experience. If they conclude that Maduro’s people just have to be punished and then the “revolution” can proceed under new management, then little progress can be made. On the other hand, if groups like the Frente Amplio can gather a consensus around a new, competitive Venezuela with institutions and a social conscience, then stability and prosperity are possible in the long term.

SaveSave