Right problem – wrong solution: The threat to the multilateral official finance system

Often priced at well below accepted market rates, Chinese official finance is a major hurdle to fair competition in the global export market. A growing number of governments are attempting to compete by circumventing OECD rules and blurring trade with aid. But adding more unfair trade practices risks the global official finance system self-combusting and ending any real chance of a lasting and fair resolution to the problem.

While delegates dressed in matching stilettos and pinstripe suits would probably spice up your average OECD meeting, real ECA and DFI cross-dressing – the increasingly blurred lines between tied ECA support and untied multilateral/DFI support – is a serious and growing problem, and one that governments need to address.

ECA/DFI cross-dressing is a reaction to a common issue for non-Chinese ECAs – how to compete with opaque official finance offerings from China, which has long been providing cheap debt, arguably at unrealistic market rates.

Until recently, that Chinese cheap-money competitive edge was offset by the quality of the technology China was peddling – Chinese products were cheap, but product lifespan was usually much shorter, and operations and maintenance costs much higher, than developed market technology.

But Chinese technology has radically improved in recent years, and cheap Chinese ECA/DFI debt is now distorting competition in the global project and trade marketplace. Non-OECD Arrangement countries like Japan and Korea have responded strongly, in effect more or less mirroring the Chinese methodology. And now some OECD Arrangement countries are following suit, circumventing OECD rules by blurring the lines between aid and trade.

While those solutions may work short-term at a national interest level, they are exacerbating the problem at an international level – in short, the level playing field for international trade, the ambition that drove the OECD Arrangement, is becoming seriously distorted.

Trade distortion growing

During the past 10 years China has transformed itself from an aid recipient into the largest official financier of developing countries. That is a huge positive development and China deserves credit for putting development of emerging market infrastructure higher on the international agenda.

But many OECD companies are rightly concerned about the completely unregulated official finance practices of China. And unfair competition has snowballed since the introduction by the Chinese government of the Going Global Strategy in 1999 and the Belt Road Initiative in 2013.

Unlike OECD countries, China does not make a clear distinction between official development finance – which includes concessional Official Development Assistance (ODA) and other forms of multilateral and bilateral development finance – and officially supported export credits. Global Chinese official finance for developing countries during the period 2005-2014 totaled $328 billion, of which $79 billion was concessional (ODA-like) $204 billion non-concessional (OOF-like) and $53 billion ‘vague official finance’, which cannot be identified as concessional or non-concessional.

Chinese official finance practices in Africa were the first to sound alarms. The annual gross revenues of Chinese construction companies in Africa reached $50.27 billion in 2016, more than three times the $16 billion gross revenues of European contractors in 2017. The economic success of Chinese construction companies in Africa is mainly attributable to the enormous official finance support provided by the Chinese government via Chexim, Sinosure, China Development Bank (CDB) and the Agricultural Development of China (ADBC).

In 2000-2017 China provided $143.3 billion of financing to African governments, which was largely used to finance public infrastructure projects. That pace of lending shows no signs of slowing. In September 2018, China announced at the international Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) it will invest $60 billion in Africa for the next three years – the same amount that was committed in 2015.

China has now become more important than the World Bank in Africa. In 2016 IBRD/IDA committed $9.35 billion to Africa, of which $8.7 billion was concessional IDA loans and $669 million was non-concessional IBRD loans. Chinese lending to African governments in 2016 was therefore three times more than that of the World Bank.

The main issues with Chinese official finance practices

Most Chinese construction companies active in Africa are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which benefit from general government support in their domestic and foreign operations. In the domestic market the SOEs have a de facto monopoly, benefit from preferential treatment and have access to relatively cheap government supported finance. Revenues generated in the domestic market can be used to cross-subsidize foreign operations.

In addition, the overseas operations of Chinese SOEs are heavily supported by the Chinese policy banks and Sinosure. The signing of a government-to-government loan implies that China “rolls out a red carpet” for Chinese SOEs to build the infrastructure with no international competition. All these aspects lead to unfair competition between Chinese SOEs and OECD construction companies across the globe. The tied nature of Chinese official finance implies also no adequate competition between construction companies. As a consequence, Africa does not get fair value for their (borrowed) money.

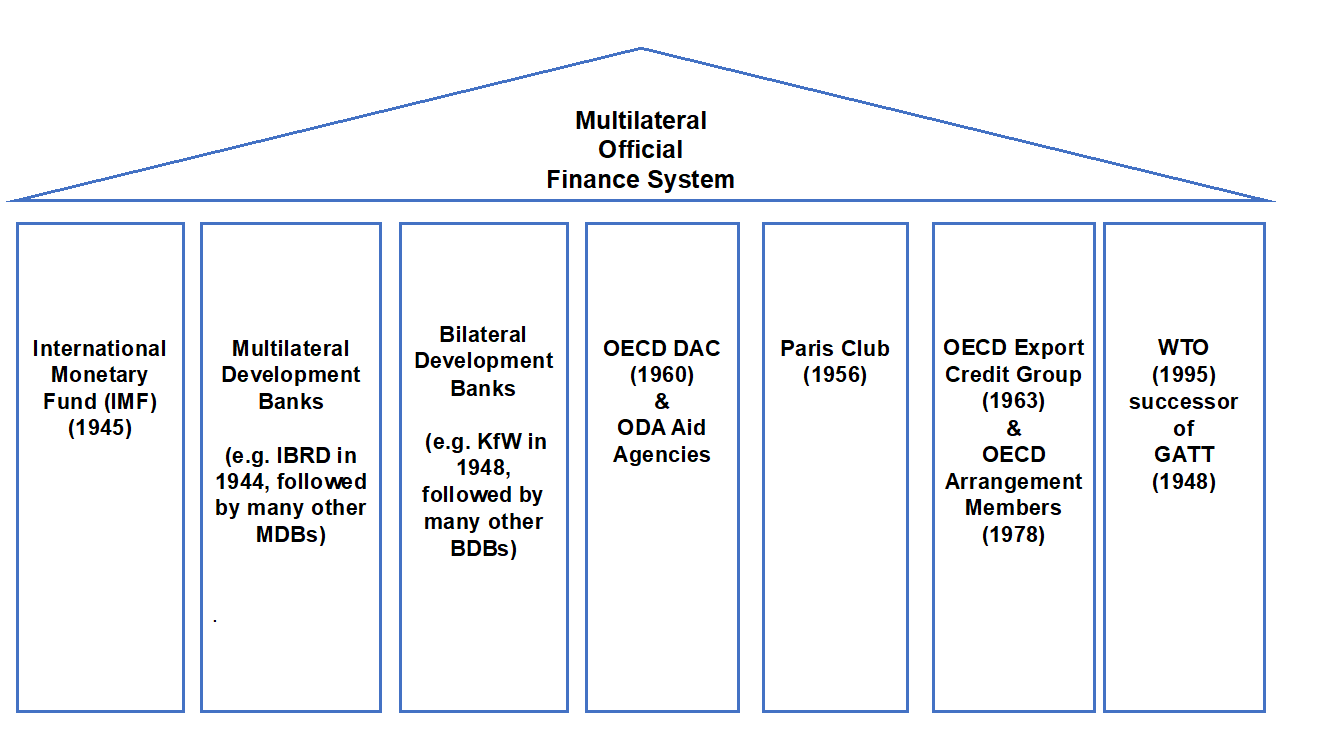

At the heart of the distortive trade practice is the fact that China does not fully participate in the unique, but rather complex multilateral official finance system for official finance to developing countries. This system was built by the international community during the past 40-60 years and is based on seven key pillars, of which some cooperate frequently and some only on an ad hoc basis.

The seven pillars include the (i) IMF, (ii) multilateral development banks, (iii) bilateral development banks, (iv) OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and agencies that provide Official Development Assistance (ODA aid agencies), (v) the Paris Club and its permanent members, (vi) the OECD Export Credit Group and members to the Arrangement on officially supported export credits and relevant official ECAs and Export-Import Banks (EXIM banks), and (vii) the World Trade Organization (WTO). Behind these organizations are the ‘guardian authorities’, usually represented by ministries of finance, trade and industry and development cooperation/foreign affairs.

The multilateral official finance system is a rules-based system to ensure an orderly functioning of international official financial markets. It includes detailed regulations for development finance, official export credits, financial and technical assistance for countries in debt distress and debt rescheduling for developing countries of bilateral debt to major creditor countries on a multilateral basis in the Paris Club.

The seven pillars of the Multilateral Official Finance system

Thus far China has refused formal membership of the OECD DAC, Paris Club and the OECD Arrangement on officially supported export credits. This has led to 10 key official finance issues that cause a severe distortion of competition:

1/ Minimum risk/market-based premiums for officially export credits agreed in the OECD to comply with WTO regulations do not apply to China. China can easily undercut pricing from OECD ECAs and create competitive advantages for Chinese construction companies. China is highly opaque about its pricing of officially supported export credits and development finance. It cannot even be ascertained whether China violates the WTO obligation that premiums for official export guarantees should not be inadequate to cover long term operating costs and losses.

Conversely, OECD governments, because they adhere to OECD minimum premiums, meet the WTO obligation and are transparent about the performance of their export credit programs through amongst others detailed reporting within the OECD.

2/ Minimum interest rates for officially supported export credits do not apply to China. Again, due to a lack of transparency, it cannot be ascertained whether China violates the WTO rule that interest rates for export credits may not be lower than the funding costs of the Chinese government. Relevant OECD minimum interest rates to safeguard the WTO obligation – the so-called Commercial Reference Interest Rates (CIRRs) – do not apply to Chinese official finance.

3/ Terms and conditions of export credits regarding the repayment profile, maximum credit periods, maximum grace periods, max support for local costs and minimum down payments (15%) and minimum interest rates (e.g. CIRR) do not apply to China.

4/ Very restrictive tied aid standards and procedures that are designed to avoid distortion of competition caused by tied aid practices do not apply to China, whereas all Chinese official finance is tied to procurement of goods and services from China. This is a huge advantage for China. Consequently, OECD construction companies cannot adequately compete against Chinese construction companies. This is one of the greatest distortive factors of financing public infrastructure projects in Africa.

5/ International anti-corruption guidelines do not apply to Chinese official finance, whereas there are many alleged and even proven cases of bribery by Chinese companies or individuals of officials in developing countries. The problem is that these corrupt business practices outside China are not well prosecuted by Chinese authorities, very likely because it often involves Chinese SOEs or individuals representing SOEs.

The situation is completely different for companies in OECD countries. Bribery of foreign officials is a serious crime, which is prosecuted by OECD authorities. Conversely, China is rated 27 out of 28 countries in the Bribe’s Payers Index (BPI) developed by Transparency International.

6/ China does not apply international best practices on managing environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks for projects in Africa, whereas OECD ECAs and multilateral and bilateral DFIs do. China applies local ESG standards of borrower countries, which are less strict, weakly implemented and poorly managed, often leading to serious sustainability issues in Chinese infrastructure projects.

7/ Chinese official finance practices are a serious threat for debt sustainability in developing countries and the IMF/WB Debt Sustainability Framework (IMF /WB DSF).

Chinese resource-backed official finance practices have a huge negative impact on debt sustainability, and that impact is growing. Non-Paris Club debt of developing countries, particularly debt to China, has risen substantially during the past years, which has already led and will lead to new debt sustainability problems in many countries. Non-Paris Club debt now accounts for more than 50% of the external stock of debt of Low Income Developing Countries (LIDCs), which complicates an orderly multilateral debt rescheduling program and IMF assistance.

The irony is that debt problems for low-income countries have, during the past 15 years, been substantially reduced by the international debt relief initiative for Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs), which included multilateral debt relief of $34.1 billion and bilateral debt relief of $38 billion, the majority of which was financed by OECD governments.

8/ China is not a member of the Paris Club and strongly prefers bilateral debt work-outs to benefit from full flexibility and no meddling from other creditors in debt rescheduling discussions. To meet government policy objectives – securing access to natural resources or obtaining overseas military bases) – China maintains secrecy over its lending and obtains better rescheduling terms than it would be able to get within a multilateral Paris Club setting. Consequently, current debt recovery practices of China are a serious threat for the sovereignty of developing countries, the multilateral debt resolution system, the preferred creditor status of the IMF and key multilateral development banks, which allows them to play their role as “lenders of last resort”.

9/ China is not a member of the OECD DAC and its ‘development loans’ lack transparency and are not in line with ODA standards and practices, which again creates advantages for China. Research from AidData revealed that approximately $79 billion of ODA-like aid and $53 billion of vague official finance was provided in the period 2005-2014. But Chinese ODA-like aid, and most certainly vague aid, cannot be characterized as true ODA because it serves mainly Chinese national interest. It is all tied to procurement of goods and services from China. Chinese official finance does not meet the ODA condition that development of developing countries should be the main objective of the financial support provided.

China would have to use substantial higher subsidy amounts to meet international (tied) aid requirements. If AidData had applied the higher OECD standards for tied aid, the highly distortive nature of Chinese official finance practices would have become more apparent. Very likely vague (tied) aid would be at least $132 billion: the sum of ODA-like ($79 billion) and vague official finance of ($53 billion).

10/ While China is not part of the entire multilateral official finance system, it benefits substantially from it. China participates in four pillars of the official financial system – the IMF, MDBs, BDBs and WTO – but thus far has managed to stay out of three other critical pillars (OECD DAC, Paris Club and OECD Arrangement on officially supported export credits).

In 2017, China received new subsidized sovereign loans from key multilateral development banks – the IBRD and ADB – totaling $4.6 billion, and currently China is one of the largest borrowers from both. The total amount outstanding of sovereign loans of both IBRD and ADB was, at the end of 2017, $32.4 billion.

At the same time China also benefits from bilateral ODA from certain OECD donor countries. During the years 2014 – 2016 China obtained new bilateral ODA funds for an amount of $4.4 billion, which is almost $1.5 billion per year.

China also benefits from official support through export credits supported by OECD ECAs. New MLT business of all Berne Union (BU) members into China in 2017 totaled around $8.6 billion, of which $2.5 billion was official export credits from BU ECAs, $1.2 billion was trade-related investment insurance and sovereign risk business, and $4.9 billion was classical investment insurance.

Furthermore, Chinese companies benefit substantially from untied multilateral and bilateral financing for projects in developing countries. In the period 2007-2017 Chinese companies were involved in $27.9 billion of IBRD financed projects, followed by Indian ($16 billion), Italian ($6.2 billion), German ($3.3 billion), French ($3.1 billion) and South Korean ($2 billion). And in the period 2008-2016 around $5.63 billion of untied bilateral ODA from OECD DAC members was used to procure goods and services from Chinese companies for projects in Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs).

Responses from OECD governments

China clearly benefits substantially from direct (i.e. from bilateral sources) or indirect (from multilateral sources) official finance support from OECD governments. Given the distortive official finance practices of China in developing countries, and its unwillingness to adhere to international best standards for official finance, this is disturbing. And since money is fungible, it could even be argued that OECD governments are unintentionally partially financing the international expansion of China and supporting Chinese distortive official finance practices.

OECD governments have responded in a number of ways, primarily via an increase in non-Arrangement business – untied investment loans or guarantees provided by OECD ECAs; development loans or guarantees from bilateral Development Finance Institutions (DFIs); equity investments; import loans and working capital facilities or pre-export financing.

All these forms of official financing have, during the past few years, become more important than regular officially supported export credits that are governed by the OECD Arrangement. Between 2013-2017 OECD Arrangement business decreased from $107 billion to $63 billion. Non-Arrangement business (including China) increased from $135 billion in 2013 to $157 billion in 2014 and has since decreased only slightly to $148 billion in 2017. The OECD Arrangement has become substantially less relevant during the past five years.

Japan and South Korea have responded strongest to the Chinese official finance competition. Japan has introduced a global strategy for “Partnership for Quality Infrastructure”. The main objectives of this initiative are (i) to support quality infrastructure investments in developing countries, (ii) to increase exports of Japanese infrastructure services to $268 billion by 2020 and (iii) to compete more effectively against Chinese official finance and construction companies.

Leading the Japanese reaction are JBIC, NEXI and ODA aid agency JICA. These institutions cooperate closely with one another to support Japanese national interest. Such a close cooperation does currently not exist in many European countries.

The US is also reacting – in October 2018 the US Senate introduced the so-called BUILD Act, which will create a new US government agency: the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC).

Many perceive this as the biggest change in US development policy in 15 years. The new agency will combine two existing DFIs (OPIC and part of the US ODA aid agency USAID) and have additional capital of up to $60 billion to increase the US impact on developing countries and combat against Chinese aid activities. It will also be allowed to make equity investments, which OPIC is currently not allowed to do. OPIC is today already providing development finance which is linked to US national interests and this is likely to increase.

The US also strongly advocates that the IBRD should substantially reduce its lending to China, arguing that China no longer needs subsidized development finance.

In November 2018 Australia also initiated a new A$3 billion facility designed to tackle Chinese competition. It comprises a new infrastructure financing facility of A$2 billion ($1.45 billion), which will include concessional loans and grants, and A$1 billion of export finance from EFIC. The facility will prioritize investments in essential infrastructure like telecommunications, energy, transport and water.

Other current ‘OECD solutions’ adding to the problem

Although in some ways positive – certainly more positive than the EU, which appears to be ignoring the problem – all these initiatives have also added to the increase in non-Arrangement business and pose a threat to the integrity of that Arrangement.

The OECD Arrangement has existed for 40 years, during which is has been quite successful in creating a level playing for OECD exporting companies and avoiding a credit subsidy race among OECD governments. Today, not only the future of the OECD Arrangement is at stake, but the entire multilateral official finance system. Unfortunately, this is not adequately recognized, which explains the lack of action by the EU and most other OECD countries.

Apart from the increase of non-Arrangement business there it is noteworthy that tied aid provided by certain OECD governments has increased substantially. In the period 2013-2017 tied aid provided by OECD governments increased from $2.3 billion to $5.5 billion. Key providers of tied aid in 2015 are Japan (76% of all tied aid reported) and Korea (12%), reflecting their response to the competition from China. Tied aid is mainly used for public sector infrastructure projects and has obviously a highly distortive impact.

Furthermore, untied aid has also become de facto tied aid. A substantial share of untied aid for LDCs and HIPCs reported by OECD DAC donors seems to be de facto tied to procurement of goods and services from the donor country – 65% on average for all DAC countries. For some countries, this figure is even higher (USA: 94,9%, UK: 89,8%, Canada: 75,2%). And despite more than 10 years of untying efforts no or hardly any progress has been made on an actual untying of aid to LDCs and HIPCs.

An alternative, more nuanced and effective approach is needed, particularly given that development finance provided by five of the nine leading multilateral development banks is de facto partially untied to relevant member countries only, and not completely untied to all countries.

Problematic is the fact that the International Working Group (IWG) for officially supported export has made no or limited progress. The IWG was established in 2012 to promote development of a new global framework for officially supported export credits. Thus far China has been unwilling to join the existing multilateral framework for official export finance or to develop a comprehensive new global framework. The attitude of China to the IWG gives the impression that China wants to continue going its own way – the benefits of ‘going global’ alone are perceived as higher than those of multilateral cooperation.

Multilateral development banks and IMF are recommended to redesign their operations

In the recent G-20 report 'Making the Global Financial System Work For All', from the so-called Eminent Persons Group (EPG), various recommendations are made as to how international financial institutions (IFIs), which include the IMF and leading multilateral development banks, can improve their operations and developmental impact in developing countries. Although the report, published on 18 October 2018, covers only two pillars of the multilateral official finance system, it has a key recommendation of relevence to all: that multilateral DFIs have to fundamentally redesign their business models and should substantially improve the cooperation with one another and other financiers. The multilateral development banks should transform themselves from direct lenders to catalysts of finance by focusing much more on:

- mobilisation of private capital

- using insurance instruments and reinsurance techniques

- implementation of joint DFI core standards among others regarding the pricing by DFIs, debt sustainability, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) topics, procurement, transparency and anti-corruption.

DFIs can learn a lot from the development of certain ‘core standards’ from the OECD ECA community. For example, the OECD ECAs developed minimum risk- or market-based premiums to avoid distortion of competition between OECD ECAs. This could be an interesting basis to not only avoid the current competition between DFIs, but also competition between DFIs and ECAs.

Another interesting feature could be the so-called commercial viability test that was designed to avoid distortion of competition between tied aid and conventional officially supported export credits. Introduction of the commercial viability test for tied aid has reduced tied aid practices substantially. Would it not be an interesting idea to use a similar approach for untied aid financing to ensure that scarce subsidized development finance does not crowd out other forms of finance that do not benefit from official support/subsidies or substantial less official support/subsidies? The approach would also help to direct highly subsidized forms of official finance to countries that have no or very limited access to market-based finance. These are the countries that are mainly dependent on development finance.

The EPG report seems to support such an approach, because it clearly states that multilateral DFI’s must place "rigorous emphasis on additionality to ensure that guarantees and concessional finance have the greatest catalytic role in attracting private capital and addressing market failures". An "additionality ranking" for all forms of official finance, not just multilateral DFI financing, is critical.

It is noteworthy that IFIs were consulted by the EPG, but this seems not to be the case for the official ECAs and ODA agencies, which explains why no reference is made to ODA, the business of ECAs and the importance of alignment of the operations of IFIs with these important other official financiers of developing countries. The EPG report reflects the silo approach of multilateral DFIs and confirms that a ‘whole of government approach’ covering all forms of official finance is key.

Concerted action is urgently needed

For all these reasons concerted action by OECD and non-OECD governments, multilateral development banks, bilateral DFIs, ODA aid agencies, ECAs and EXIM banks, and the guardian authorities behind these official finance agencies, is urgently needed to create a global level playing field for internationally operating construction companies.

A ‘whole of government’ approach must be developed, which implies that government officials, active in the various pillars of the multilateral official finance system, will have to cooperate closely with one another. The framework should cover all forms of official finance for developing countries – export credits; ODA; tied aid; untied investment loans and guarantees; development loans and guarantees from multilateral and bilateral DFIs; other forms of official finance (e.g. equity investments); and debt rescheduling for countries in debt distress. The current focus by the IWG on just conventional export credits is too narrow. The G20 EPG report on IFIs lacks also a comprehensive official finance approach.

The joint action plan is also of utmost importance to maintain and restore the unique multilateral system for official finance to developing countries. The system is being eroded by the increase in tied aid, unregulated official finance and the untied aid practices of various OECD countries. Chinese practices have triggered a renewed race to the bottom of all forms of official finance at the expense of scarce government budgets and tax-payers’ money. And if, in the short term, no adequate action is undertaken, it may even lead to a complete collapse of the multilateral official finance system.

Last, but certainly not least, concerted action is also in the interest to enhance international efforts to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), maintain the integrity of IMF/WB Debt Sustainability Framework, improve debt sustainability of low-income developing countries and ensure an orderly multilateral management of public debt problems of developing countries.

An enhanced multilateral official finance framework will assist in a better alignment of various forms of official finance (both from multilateral and bilateral sources) with other forms of public and private sources of capital for development. Such a better alignment is needed to avoid that for projects in developing countries (highly) subsidized forms of official finance replace or crowd out other forms of finance that do not need or benefit from substantial less official support. Subsidized development finance should be complementary to the market and not the other way around. The agenda is therefore important for the development of successful DFI mobilization strategies that truly catalyze additional capital and not replace other existing forms of capital. It can therefore contribute to enhance aid effectiveness and aid efficiency. Given the magnitude of various global challenges faced today, a single pillar or silo-approach can no longer be afforded. Bridges need to be built, because 1+1=3!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Priority issues for a global framework for official finance

- Common regulations on all forms of tied aid and (partially) untied aid (e.g. ODA and multilateral or bilateral development finance), including an “additionality ranking” of all forms of official finance.

- Common risk-based pricing system for all forms of cross border trade- or investment-related official finance / guarantees.

- Minimum interest rates for all forms of cross border trade- or investment-related official finance / guarantees.

- China should be strongly encouraged to become a permanent member of the Paris Club and to fully adhere to the IMF/WB DSF and OECD guidelines on sustainable lending to developing countries.

- Common terms and conditions on maximum repayment periods, maximum grace periods, repayment profiles, minimum officially supported interest rates & premiums, maximum amounts for official support for all forms of cross border trade – and investment-related official finance/ guarantees.

- Adequate and verifiable transparency on all forms of official finance with priority to (i) tied aid, (ii) export credits, (iii) untied development finance (multilateral and bilateral ODA and non-ODA), (iv) untied investment loans and guarantees and (v) other forms of official finance (e.g. equity investments).

- The UN SDGs, which include infrastructure, climate change, partnership for development and the importance of mobilizing private capital, provide the direction for what needs to be done, so it is now primarily a matter of bringing people and organisations together and building the necessary bridges between them.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This article is based on a study conducted by Paul Mudde, consultant at Sustainable Finance & Insurance, for the European International Contractors. The complete report with detailed background information and potential action points can be found on the website of the European International Contractors via the following internet link: https://www.eic-federation.eu/sites/default/files/paragraph-files/sfi_study-china-official_finance_practices.pdf.

It should be noted that the views and opinions expressed in this article and the study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the European International Contractors or TXF Media.