Indonesia’s coal-fired reckoning

ADB’s ETM and the $20 billion I-JETP initiative are currently negotiating the ambitious task of retiring Indonesia’s young fleet of coal-fired power plants. While the success of these deals remains to be seen, finding a way to replace the country’s base-load power with renewables is a regulatory, political and policy challenge in itself.

Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s biggest emitter, trumping the competition by almost 300 million metric tonnes of CO2 in 2021, according to statista. To achieve net-zero by 2050, the country has set some lofty targets for its energy transition – like peaking power sector emissions by 2030 at no more than 290 million tonnes (MT) and transforming the energy mix from a 82:18 fossil fuels to renewables ratio of to at least 70:30 by 2030.

Coal dependency poses a major barrier to this goal. The country has 39 billion tonnes of coal reserves which a young fleet of coal-fired power plants (CFPP) is currently using, accounting for 60% or 40GW of installed energy capacity.

Power is over-concentrated and outstripping demand. The 117 CFPPs the state-owned, sole offtaker PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) is planning to build will be over capacity in a year given only 65% of the population has electricity access, and this drops to as low as 30% in certain provinces. Jannata (Egi) Giwangkara, senior project manager at Climateworks Centre, compares the situation to a five-seater car: “Four out of five of the people in the car are fossil fuels, and you’re the only renewable. If you want to invite more renewables in, you’ll have to kick some people out of the car.”

A low-carbon future

A financially sizeable step is already being taken towards a low-carbon future, fuelled by both MDBs and IPPs. Two landmark MDB-backed projects announced at the G20 meetings in November 2022 are aiming to bolster the first step to Indonesia's sustainable future – retiring CFPPs. The first is the ADB energy transition mechanism (ETM) which will, in part, oversee the retirement and repurposing of CFPPs in collaboration with the government and PLN.

For its pilot project, ADB signed an MOU with Cirebon Electric Power to explore the retirement of the 660MW Cirebon 1 CFPP. The present deal does not change the ownership structure for the 12-year-old plant, a key power supplier to Jakarta with a 30-year supply contract with PLN, but will refinance the current loan with a $250 million to $300 million facility on condition that it be taken out of service 10-15 years before the end of its 40-50 year useful life.

The legal and commercial negotiations for the ETM are long discussions and with the Indonesian presidential elections upcoming in February, an anonymous source revealed that it is unlikely any deal would close before Q2 2024.

According to Yuichiro Yoi, principal investment specialist at ADB, the “planned transaction is designed to be a replicable model that can be applied to other IPPs in Indonesia”. This aim of replicability may be the reason ADB was careful not to attach Asia’s first coal retirement financing – the 244MW ACEN South Luzon plant – to the ‘official’ ETM programme, despite consulting on the deal: it was very much a product of its home market, and might not apply elsewhere in the region.

Another G20 announcement, the I-JETP, captured headlines with its ticket size: a $20 billion blended finance initiative aiming to phase out existing plants and cease the issuance of new permits. Up to $10 billion has been committed by GFANZ, a global coalition of private institutions with net zero ambitions, and the rest by the International Partners Group (IPG) composed of the EU, UK, USA, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, Denmark and Norway.

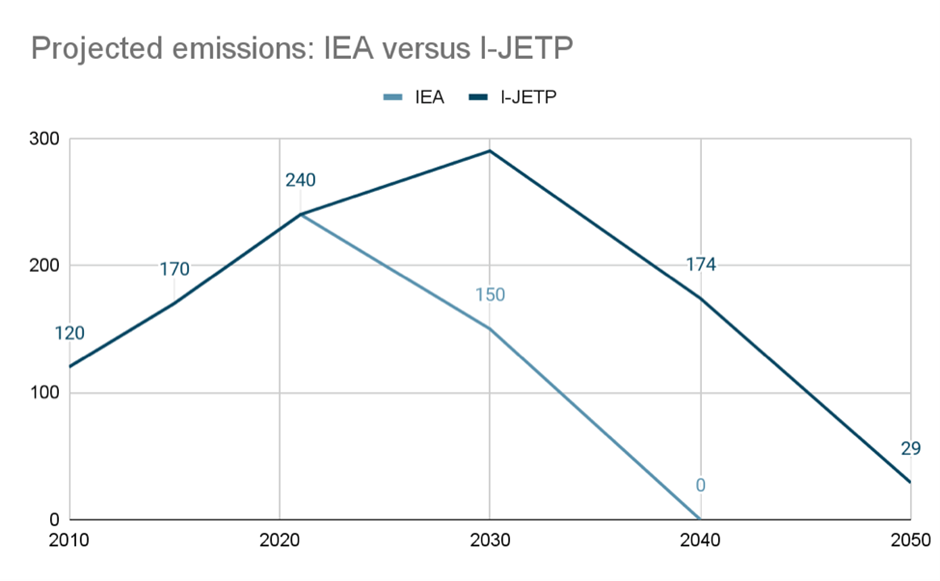

Crucially, I-JETP is trying to halt the existing pipeline already approved by PLN in its Electricity Supply Business Plan 2021-2030 (RUPTL). However, I-JEPT has no requirement for the Indonesian government to stop coal plants under construction or captive plants from going ahead. That distinction, as visible in the graph below, puts the I-JETP emissions plan at odds with the IEA’s roadmap to net zero for Indonesia.

Part of the reason the government is allowing these projects is for industrial zones that need the ‘cheapest’ electricity with low upfront costs, but this is drawing criticism from both domestic and overseas energy watchdogs, says Giwangkara.

Replacing coal

In order to retire CFPPs, project developers will need to provide sufficient base-load power replacements to ensure the energy supply does not fall short. Solar and wind are a possibilty – PLN is reportedly tendering out a floating solar and a hybrid solar IPP to international investors, based in the new capital city Nusantara.

However, geothermal and hydropower can arguably provide more scalable base load replacements. While these projects require longer-term loans to cover feasibility studies, Indonesia already derives the majority of its renewable energy from hydropower and, being surrounded by the Ring of Fire, it also has 23.7GW of potential for geothermal development.

A remaining crucial hurdle is that PLN does not currently allow for investors in coal retirement initiatives to automatically become investors in new renewables projects on a particular site. Instead, it must open up the tender and go through a new procurement process with other investors able to participate. This is less appealing to private investors who may already be cautious around investments in CFPP and how Cirebon resolves this remains to be seen.

An abyss of regulation is stifling a renewables wave in general. The government proposed a draft law on new and renewable energy in 2019, but over three years have passed with nothing produced yet. Without an overarching policy framework, projects are subject to individual, inconstant regulations. In 2018, the government released the first rooftop solar regulations but constant amendments meant that corporate and commercial buyers couldn’t sell the generated electricity for more than their existing electricity capacity subscriptions – meaning if they had 15kV of installed capacity then they could only produce 15kV.

This poor policy design also affects pricing. The government introduced a feed-in tariff over five years ago but has since revoked it, switching to local generation cost pricing. Having renewables on par with local generation costs without additional ceiling prices does not provide much incentive for international developers.

This is not necessarily due to a lack of budget: Indonesia was the seventh largest country subsidising coal and electricity in 2021, handing out approximately $24 billion that year according to IEA data. But with PLN already locked into existing long-term, coal-based electricity contracts, it is not in a financial position to subsidise alternative assets alone.

The Presidential Regulation No. 112 of 2022 concerning the Acceleration of Development of Renewable Energy for Electric Power Supply released in September 2022 was able to resolve some challenges. Firstly, it allows for the direct selection of renewable energy proposals from IPPs, easing some of the burden of the bidding process. It also reintroduced electricity pricing schemes, this time enabling PLN to agree to higher ceilings for specific offtake prices in areas where the electrification rate is low. It also crucially provided a legal basis for the implementation of CFPP early retirement initiatives.

A cautious government

Getting the government to accelerate renewables is a big challenge. The growing capacity of overseas coal exports to China, India and other Asian nations has accounted for more than half of Indonesia's coal production in the last decade. Giwangkara warns of the 'old paradigm' trap: “Older generations of decision and policymakers still think that coal and fossils are cheap and should make the most of them while still having their economic values.”

However, times are changing says Giwangkara: “They [decision makers] are watching some fossil fuel companies build renewables and pivot their business towards EV, energy storage, and critical mineral extraction. Some incumbent industries have even realised the transition is inevitable and are targeting sustainability and net zero targets.”

A senior leader at PLN recently announced that the next RUPTL will go beyond the previous one, jumping up the target for renewable energy capacity from 51% to around 70% (2023-2032). With this ambitious plan, Indonesia has an opportunity to capture the heat of the southeast Asian clean energy development market: if it falters on regulation, it risks losing that business to its neighbours in Vietnam and the Philippines.