Untied commodity lending: A critical ECA space

The rise of untied lending in the export finance market has been apparent in recent years. But, given the role metals and critical minerals are playing in accelerating energy transition, ECAs are upping support to the sector via royalty providers and by extending untied finance to traders.

The ECA model is experiencing the pangs of seismic change. For several years, it has been besieged on all sides by outdated regulation, the demands of national interest, and the plentiful criticisms offered by clients who want more support than ever. With war in Ukraine swiftly following on the heels of a global pandemic, the rhetoric around what ECAs should be doing for the exporter community and domestic industries has amplified to unprecedented levels.

Within all of this ECAs have quietly sought to establish themselves in new markets through untied lending facilities – a financial instrument which provides greater flexibility than traditional export credits by leveraging future business and trade flows. This development was highlighted significantly by Trafigura's recent announcement of an untied $800 million loan agreement, guaranteed by Euler Hermes, to secure around 500,000 tonnes of non-ferrous metals for German industry. The five-year facility was arranged by Societe Generale and syndicated with seven other banks - namely: DZ Bank, Helaba, KfW IPEX-Bank, Natixis, Raiffeisen International Bank, Santander and Standard Chartered.

Expect to see similar deals emerge in the course of the next year, with several traders in the market for untied finance. It remains to be seen if ECAs can maintain a long-term role in the commodities space, but their involvement is significant in the context of growing international competition for a limited stock of physical raw materials.

Without question, ECAs are now showing a growing interest in securing commodities from major traders on behalf of their respective domestic industries. This objective is being achieved in large part through direct lending that is not tied to specific export finance deals. These untied facilities are part of a new push to show markets that ECAs (both OECD and non-OECD) are not constrained by the OECD Consensus. Several different factors have influenced this development; the emergence of consecutive black swan events has added complexity to a risk-laden industry, and the demands of the green energy transition have encouraged states to use every weapon at their disposal to secure the metals and critical minerals required for battery-making and more generally electrification.

The significance of the OECD Consensus’ long-term inadequacy should not be underestimated. In the absence of adequate reforms that would create a level playing field with exporters in China and India, it is not surprising that European ECAs have looked to untied facilities that fall outside of the scope of the OECD. One consequence of this development could be an ECA model that has a much wider role in securing national interest than simply promoting exports.

To set the scene for these changes, a number of ECAs have published new frameworks, initiatives, and memoranda that will serve to guide their ambitions in future. Many of these were prompted by the rigours of COVID-19, at a time when ECAs provided extensive payment holidays and liquidity facilities to struggling businesses. NEXI established its LEAD Initiative in December 2020 to underwrite JPY1 trillion ($6.7 billion) by 2025 in projects that promote sustainable goals. JBIC launched its Global Investment Enhancement Facility to support projects in overseas markets. SACE has its Push Strategy, first published in 2017, that explicitly provides for untied investment in strategically important foreign projects.

Many ECAs are now actively inviting proposals from foreign countries that do not involve direct investment in their domestic industries, but rather strengthen the supply chains that those industries benefit from. JBIC and Export Finance Australia have said that they will consider making equity investments in project financing rather than simply shouldering debt or providing export credits. At the core of these initiatives is a desire to show that ECAs can offer a range of flexible measures that will support their domestic clients.

For any exporter, the key question is whether this raft of agreements has materially impacted the ways in which ECAs operate. Ambition is admirable, but what new opportunities for deal origination could this lead to? SACE’s Push Strategy has been in place for several years now, and the data collected by TXF Intelligence reflects its influence. The Italian ECA provided $1.29 billion in buyer credits in the first half of 2022, and just $393 million in all of 2021. This is a steep fall from $12.6 billion in 2020 and $9.7 billion in 2019.

TXF has recorded a single buyer credit deal by SACE in Asia this year, suggesting that its business there is comprised almost entirely of untied lending. An example will serve to highlight how this benefits Italian industry: in March of this year, SACE signed a $50 million three-year untied credit line with Archiridon, a Greek construction firm, and HSBC. Proceeds will go towards general financing needs and corporate purposes. As part of the agreement, SACE will arrange meetings between Archiridon and Italian SMEs that show interest in becoming suppliers. Archiridon has committed to increasing its procurement from Italy. In another development that may help to raise standards in the export finance space, the deal was concluded under the sustainability-linked loan principles, as defined by the Loan Market Association (LMA).

Environmental KPIs include the use of retrofit engines and renewable energy sources. In the absence of specific project KPIs, untied lending offers an opportunity to improve ESG governance in export finance. While sustainability loans are still fraught with issues relating to reporting and manipulation, they encourage companies to develop their social responsibilities with meaningful financial incentives.

In the context of untied lending and its advantages, commodity trading represents a viable new frontier for ECAs to explore. Minerals will continue to grow in importance as countries seek to ramp up production of electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable power sources in the wake of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Untied lending allows ECAs to create open-ended agreements for supply without directly investing in physical assets. Industry sentiment suggests that this topic is set to ignite over the next year, and already several deals have set the template.

The Korean ECAs have already shown significant appetite for commodity-linked deals. In December 2021, Kexim closed a $150 million bullet loan with Trafigura in exchange for a secure supply of base metals to Korean corporates. A similar deal with SQM, the Chilean chemicals company, was sealed in September 2022. A fund of $100 million was established, with $55 million in loans and $45 million in guarantees, and in return SQM will provide Korea with lithium for battery manufacturing. Over the next ten years, Korea will receive a supply of metals worth up to $470 million. Finally, KSURE has expressed conditional support for a $140 million loan to the Mount Peake vanadium-titanium-iron project in Australia. Euler Hermes and Export Finance Australia are also interested. In this case, the ECAs are providing coverage that is tied to a project, but it is linked to a long-term offtake agreement for minerals rather than direct investment in the mine.

ECAs are no strangers to project financing in the mining space, but their involvement is usually limited to the export of goods for the mine. It is uncommon for them to seek out offtake agreements, but the evidence of the past few years suggests that ECAs are looking for small mines in need of financing abroad as an alternative to developing expensive new extraction sites. In 2020, the Austrian ECA OeKB guaranteed a $75.1 million debt package for the Sangdong tungsten mine in South Korea in a deal that secured an offtake contract for Plansee, the Austrian metals component producer. Sangdong was closed in 1992 as a result of Chinese consolidation in the tungsten markets, but Almonty Industries were able to restart production as a result of Austrian ECA involvement.

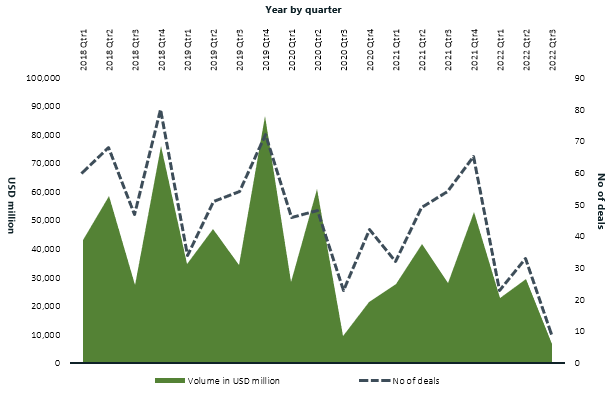

If ECAs can secure long-term offtake relationships with the biggest traders, then the opportunities for growth are enormous. From 2018 through to the first half of 2022, TXF Intelligence has recorded more than $400 billion of commodity finance deals conducted by traders (see graph below). This figure only reflects the volume of deals that were made public. The biggest names, including Glencore, Trafigura, Gunvor, Mercuria, and Olam International have each been involved in more than $20 billion of deals in that time. While this is a crude measure of opportunity, at the very least it suggests that ECAs are at the foot of the mountain when it comes to commodity financing.

The most noteworthy aspect of these ECA deals, whether they are untied or related to offtake agreements, is that ECAs are inserting themselves into the commodity supply chain. This trend will only grow as more and more ECAs announce their intentions in the commodities space. Export Finance Australia has operated a $2 billion critical minerals facility since 2021, over half of which has been distributed already. In September, US Exim and K-SURE signed a co-financing agreement for new projects in the critical minerals space. Just last week, EKN announced a new credit guarantee scheme for investments in foreign schemes that produce raw materials for Swedish companies.

Significantly, this was possible because the Swedish government expanded EKN’s mission beyond pure exports. The shift into the world of commodities is indicative of a broader change in the ECA model. As yet, it remains unclear whether this evolution will settle anytime soon. At present the role of the ECA seems amorphous. It certainly needs to be flexible as new demands are placed upon it, and untied lending suits this new agenda. For now, we can safely say that commodities have been added to the ECA to-do-list. But what might come next? Hydrogen is high on the financing agenda - but perhaps not as high as defence.